Subalternation

According to the Ancients, Schoolmen, and Moderns

Subalternation is defined:

SaP⊃SiP

SeP⊃SoP

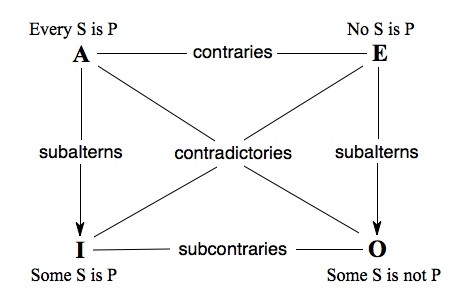

The Square of Opposition, as pictured on the right, to the bottom of S. Albertus Magnus, depicts the respective logical relationships between certain categorical propositions. To define our functors briefly outlined above, we have:

A functors are of the form: All S are P

E functors are of the form: No S are P

I functors are of the form: Some S are P

O functors are of the form: Some S are not P

It is clear to see that, if the proposition "Every A is B" is true, then "No A is B" is false, therefore its contrary, "Some A is B" would be true. Subalternation relates the universal functors to the particular ones.

According to the Ancients

Aristotle discusses the Square of Opposition in De Interpretatione. Aristotle says: "from this it is manifest that to every affirmation there is a negation opposed, and to every negation an affirmation" (17a26). This would constitute the rules of contraries and sub-contraries (a medieval term); it is also an essential axiom for the law of excluded middle. Regarding the rule of sub-contraries, Aristotle further states:

"But when the contradictions are of universals not signifying universally, one is not always true and the other false, for it is at once true to say that man is white and man is not white, and man is beautiful and man is not beautiful" (17b29).

Sub-contraries have an opposition in falsity, but not in truth. Therefore, the statements "Some man is just," and "Some man is not just," can at once be true in contingent matter, but not in necessary matter. I mean, if all men are risible, then some men are risible (rule of subalternation), but since all men are risible, some men not being risible is impossible.

However, Aristotle does not explicitly mention the rule of subalternation in De Interpretatione, but does in his Topics, stating:

"Look also at the genera of the objects denoted by the same term, and see if they are different without being subaltern, as (e.g.) 'donkey', which denotes both the animal and the engine."

Under Construction